missing poster for Kampusch age 10/AP/unattributed

missing poster for Kampusch age 10/AP/unattributed

In 1998, 10 year old Natascha Kampusch was kidnapped by Wolfgang Priklopil on her way to school in Austria. She was kept locked in his home, often in a small cellar in the basement, and emotionally and sexually abused for the next eight years. During that time she was often frequently denied food and suffered from malnutrition resulting in her being almost the same weight when she was found as she was when she was taken at age 10. The malnutrition impacted her physical and brain development as much as the sexual and emotional abuse impacted her emotional one. According to Kampusch, Priklopil referred to her as his “sex slave” and himself as “the master”. He made her clean his house half-naked when he was not humiliating or violating her in other ways. In 2006, she finally escaped when Priklopil took a phone call while she was outside in the garden cleaning his car. Despite her repeated calls for help as she ran through the neighborhood where she had been held, no one actually called the police, until Kampusch stopped at a 71 year old woman’s house and asked her to use the phone to call the police. The case sent shockwaves of horror throughout the world and an SVU episode was loosely based on her story. Wolfgang Priklopil committed suicide shortly after her escape to avoid prosecution. When he died, so did the information about why he did what he did and how he had gotten away with it for so long.

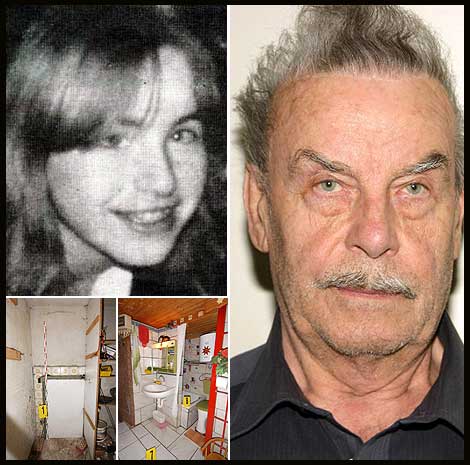

Kampusch revisited her story recently when another girl, Elisabeth Fritzl, was discovered being held captive in a similar hidden cellar, by her own father for 24 years, also in Austria. Josef Fritzl did not commit suicide and continues to harass his daughter from behind bars. According to his friends and neighbors there had been some suspicions about his behavior and renters had also noticed things, but no one looked into it further. His wife, Elizabeth’s mother, continues to deny any knowledge of it though she helped raise several of Elizabeth’s children by Josef Fritzl.

Josef Fritzl, last known image of Elizabeth & the cellar apartment were he kept her for 24 years/unattributed

Josef Fritzl, last known image of Elizabeth & the cellar apartment were he kept her for 24 years/unattributed

Kampusch shared her stories of rape, sexual humiliation, and captivity from childhood with Elizabeth in the hopes of showing her and the world that you can survive horrendous sexual abuse and enslavement. Telling her story, also prompted Kampusch to write a book about what happened to her to help other women and girls surviving childhood sexual abuse and rape. The book, 3,096 Days, chronicles Kampusch’s 8 years in captivity, focusing on her survival skills and her emotional process throughout the abuse. The book was published this month and is the first time Kampusch has told her story to the world.

When Kampusch first escaped, she did several interviews but was wary of news reporters digging into her abuse history. In an interview with the Sunday Times, she spoke about feeling violated by people looking at the small room where she had been kept and picking over the details of photos from Priklopl’s home and police reports in the national news:

“… above all, I’m annoyed about the pictures of my dungeon, because it is nobody’s business. I also would not look into the living rooms and bedrooms of other people. Why should people be able to open up a newspaper and look into my room?

…

The media interest is too much, but on the other hand through this fame I have some responsibility and I want to use to this advantage to help other people, to make a foundation and do charitable projects. For example to help lost people who were never found like me. And I want to work with the hungry [in Africa].” (Sunday Times 2006)

Like many survivors, Kampusch initially minimized her abuse and tried to keep details to herself. Her limited education, provided through newspapers and radio stations given to her by Priklopl also gave her a sense of worry for “the starving kids in Africa” despite having never seen any and actually having been motivated by her own starvation at the hands of her abuser. She later referred to them as primitives while again making a connection to her own thoughts as equally so because of hunger. The racism she expressed, especially in the context of being referred to as a slave by her abuser for 8 years makes one wonder about the racial overtones of her abuse and the connections between racism and sexism even in the life of an blonde blue-eyed Austrain girl who had likely never met any people of color or learned very little about the world before or during her capture and assault.

When she talked about gender, she also seemed to have internalized messages that women were weaker and/or powerless:

And this female lack of power that I couldn’t do anything against him.

These thoughts too, likely came from Priklopl to both subdue her and groom her for ongoing abuse. These gender disparities also made her identify with Priklopl’s mother and worry about how she would get on in the world if her son was prosecuted. At the same time, Kampusch talks about promising herself that when she got older and stronger, she would escape.

Much of her story about how he convinced her that he was harmless and that her parents did not love her, in those initial interviews, follow a similar pattern to the stories other kidnapped children and trafficked child sex workers tell. In these stories, kidnappers tell children their parents gave them permission and/or are coming to pick them up as soon as they pay a ransom or get a check they need or new job, etc. and then after time goes by kidnappers switch the story to say parents are still unavailable, finally following up with stories of how parents no longer want them, abandoned them, or even are dead all the while slowly grooming the children to trust or become dependent on them so that they will resign themselves to the abuse. In Kampusch’s case, Priklopl not only did all of this, but also forced her to take a new name to divorce her from her past and possibly hide her better.

Kampusch/The Star/unattributed

Kampusch/The Star/unattributed

Now Kampusch speaks about her abuse with the insight of someone who has had time to talk and heal. She no longer looks at people’s interests in her case as invasive but rather an opportunity to help others avoid or survive abuse in their own lives. In place of her the survival skill of minimizing abuse, is a forthright tone that waivers at certain memories but is committed to telling her story and moving forward. While she still shows signs of what I would consider unhealthy attachment to her abuser, she bought his car and his house, she is trying her best to tell a story she spent 8 years being trained never to tell and she is doing, not for fame or fortune, but to help other women and girls.

Two other books about the incident were published prior. In 2006, an English-language book Girl in the Cellar was published by two journalists who had worked part of the case. Kampusch’s mother also published a book about her own story looking for her daughter two years later. Both books were controversial because Kampusch disputed the material in the former and even threatened suit. While her mother’s book capitalized on the media attention Natascha’s escape was receiving but did only tell her own story. Though both mother and daughter had a strained relationship at the time, Natascha did attend her mother’s release party and has never disputed information in her mother’s book.

So far, the 3,096 Days is not available in English and though there is a planned movie based on the book to be released in 2012, it is unclear if there will be an English language version of the film either. While there are things that are specific to Austria, like the basement cellars that so many predators seem to be using to hide their assaults on women and girls, the story of surviving child sexual abuse and rebuilding one’s life is unfortunately universal. While I have always worried about the way these two girls-now-women’s stories have been turned into spectacle by the media, I do think that hearing their stories in their own words is critical for rape survivors and people invested in ending child sexual abuse, rape, and torture of women and girls. There are lessons to be learned in how and why these men were allowed to continue abusing women and girls, despite some public unease, signs of potential involvement, and in Fritzl’s case previous conviction or suspicion of sexual assault. If we stopped talking about these cases as exceptions dominated by monsters and started asking how these men succeeded and how our investment in women and children’s inequality helps pave the way for heinous acts of violence we might make huge leaps forward in moving beyond the non-profit industrial complex, which, mind you, helps save women’s lives, to a world safe for young girls to walk to school or live in homes without every needing to fear their own fathers or male relatives. And while many of us are lucky to have lived in such homes and maybe even walked to school without knowing about predators, the fact is many of us were not and are not.

If an English-language version of the book comes out, I will update this post and/or announce it. (If you want to know more about Kampusch, there is an extensive link list at the bottom of the wikipedia page on her, though of course I would tell you to read those links and their sources directly, not just rely on the wikipedia page itself.)

Related Articles

- Austrian kidnap victim draws crowds to book reading (omg.yahoo.com)

- Kidnap victim describes ordeal as starved, sexually-abused ‘slave’ (today.msnbc.msn.com)

- Kidnap Woman Details 8 Years of Slavery, Abuse (abcnews.go.com)

- Austria kidnap victim: ‘I wanted to start a new life’ (today.msnbc.msn.com)