I’ve been trying to make these black herstory month posts about groups, collectives, the little known, or some of the unknowns in the well-know . . .

(Black Women Directors Honored by the BHERC 2007)

(Black Women Directors Honored by the BHERC 2007)

Today, as part of my commitment to also shine a light on African American female film directors, I am going to switch gears slightly and focus on a single artist. Since black women film makers are often completely invisible in Hollywood and in the popular imaginary, I think it is important to give each of these women there own space to shine as individuals who make up a collective body of cinematic knowledge and sacrifice. So every Friday for this month, and maybe into the next, we are going to spotlight a black woman director.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Cheryl Dunye

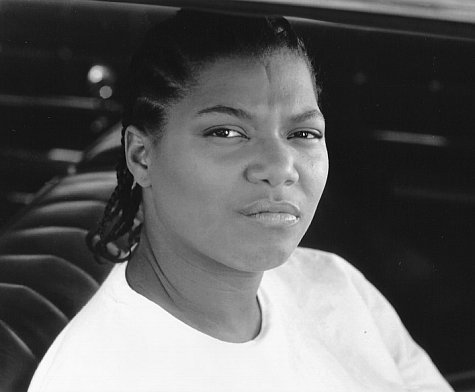

(Cheryl Dunye/ unattributed)

(Cheryl Dunye/ unattributed)

Cheryl Dunye’s first feature length film, Watermelon Woman, is largely credited as the first feature length film to star an out African American lesbian. While the film is significant for this reason alone, it has always interested me because of its  critique historiography and cinema. Watermelon Woman tells the story of a struggling black filmmaker, Cheryl, who is researching an unnamed actress in old Hollywood who was having an interracial relationship with a white film star. Cheryl, played by Dunye, encounters multiple layers of oppression in attempting to uncover the story while also fielding the criticism of her black lesbian cohort for her own interracial relationship. Despite the fact the Fae Richards appears in many small parts throughout the golden age of hollywood she is neither credited in most, accept once as the “watermelon woman,” nor remembered. As a black woman, her career is both significant, because of the number of films she was in, and insignificant, because of the roles and position of black actors in mainstream Hollywood. Thus Cheryl is forced to try and piece together the woman’s life from old photographs and rapidly decaying film.

critique historiography and cinema. Watermelon Woman tells the story of a struggling black filmmaker, Cheryl, who is researching an unnamed actress in old Hollywood who was having an interracial relationship with a white film star. Cheryl, played by Dunye, encounters multiple layers of oppression in attempting to uncover the story while also fielding the criticism of her black lesbian cohort for her own interracial relationship. Despite the fact the Fae Richards appears in many small parts throughout the golden age of hollywood she is neither credited in most, accept once as the “watermelon woman,” nor remembered. As a black woman, her career is both significant, because of the number of films she was in, and insignificant, because of the roles and position of black actors in mainstream Hollywood. Thus Cheryl is forced to try and piece together the woman’s life from old photographs and rapidly decaying film.

Her first clandestine efforts with cinematic archives is a failure precisely because the “watermelon woman” was not considered significant enough to document. Cheryl’s archival mismatches shine a light on what many historians of queer culture have argued, that often we are left with rumors, letters, journals, and the keen since of gaydar to find our way.  Add in another layer of intersecting oppression and becomes that much harder.

Add in another layer of intersecting oppression and becomes that much harder.

Moving away from Hollywood as her source, the director then confronts racism in the queer and feminist archives, neither of which have bothered to spend a significant amount of time documenting the lives of black women. At the feminist archive, Cheryl is given a single box of unsorted materials and chastised for trying to use the documents within. At the queer archives she confronts both the absence of black herstory and the overwhelming emphasis on gay men’s history. In these moments she exposes the problems of the left in which race, class, and region often remain hegemonic even as the center shifts toward women or queer culture, which also continues to have the dual problem of addressing women and transpeople equally.

Failing once again to find any trace of our shared and overlapping histories, Cheryl goes to the family members of the Watermelon Woman’s possible girlfriend. At first, they are excited to meet her but as soon as they discover her film is about lesbians, they back out. Family members claim they know nothing, despite having photos of the two together, or that they were coerced in their interviews. These fictional encounters mirror the homophobia surrounding the later release of Looking for Langston (1988 ) which was rejected by the Hughes’ family and barred from referring to Langston Hughes himself or his sexuality by the estate. In the latter case it was black homophobia that got in the way, in the Dunye film it is white homophobia.

The basic premise of the film, then forces us to confront the ways in which neither archives nor history are neutral but rather filtered through the same biases that govern our society. Instead of making a binary argument in which racism is the sole problem and progressives are all liberated, Dunye takes a critical to eye to the ways that multiple groups have failed to think and act intersectionally. In so doing, she clearly documents how our collective failures have robbed us of a rich mutlicultural, multi-gendered, multi-desiring, vision of our history that is much more accurate than the tightly boxed up ones we deal with now.

As Dunye put it:

By the end of the film it’s back in your face saying the Watermelon Woman is a fiction, I made it all up. What does that mean now, you have to do something (interview)

In other words, it is our task to confront both the oppressions of the past and the present in order to tell and display a more complete history of our world and the cultures within it.

Though Watermelon Woman did well on the independent circuit, Dunye also expressed concern about funding and commitment to the film. In a comment that we will see is all too typical of black women’s experiences in Hollywood, Dunye lamented how little funding she was able to garner from either the black community/ies or the queer one(s):

I’ve given up my life for the last four years and would have hoped that more progressive folks and those kind of communities of labels of identity politics and race politics, etc. would have made it out to the film or helped with the film or supported the film, but they haven’t so there’s a lot of work to do. (ibid)

While many independent filmmakers struggle to make their films and get distribution, one of the things that has plagued black cinema in particular is the failure to garner funding from within the black community or the usual channels accessed in Hollywood by independents. Part of this has to do with the limited resources available to the black community as opposed to the often affluent white first time directors. It also has to do with major structural inequities that make it easier for dominant culture to get loans, lines of credit, and introduced to other funding sources through affluent networks that are largely closed to African American, and especially African American female directors. A final layer of removal comes in the erasure of the black queer experience from both mainstream black culture(s) and white queer culture(s). Meaning that while Dunye expected to get funding and support from both black and queer culture, her subject matters seat in the intersection prevented such support. Worse, for certain segments of the queer of color communities, interracial dating is itself a controversy further removing Dunye’s film from a place of support.

Dunye is critical of the way the industry often requires black artists to seek white patrons, but astute enough to point out how this too is a historical process:

. . . most of the cast is of color and a lot of the producers aren’t. There are moments when I felt disempowered but with it but there were moments in history, looking back at the Harlem Renaissance which some of my film does look back to and you know, that’s how culture gets made with black people. Yes we have to break that chain but yes we have the kind of culture that functions on that philanthropy. (ibid)

Her words echo those of artists and intellectuals like Cullen, Baldwin, Dunham, and Hurston all of whom had scathing critiques for the way that philanthropy worked during the Harlem Renaissance particular within the queer community and across gender lines.

At the same time, Dunye is more philosophical about the possibilities embeded in philanthropy:

Being a token is, as Essex Hemphill said to me, “when you are given a token or made a token what do you do? you take a ride, you ride with it.” I feel like a lot of the kind of people that I worked with believed that themselves as well as I did in the sense of moving forward. I think we all got something out of it whether we work together again or not. There’s a certain sense of empowerment in creating art and there’s a certain sense of disempowerment in creating art and culture. (ibid)

The positive aspects show in all of Dunye’s films. The success of Watermelon Woman in particular had a lot to do with  intersectional support. Much of the minimal budget for Watermelon Woman came through Women Make Movies, a feminist media group that helps ensure the production, promotion, distribution, etc. of female directors and films by and for women. As the fiscal sponsor, WMM helped Dunye secure funding she would not otherwise have been able to receive though they did not provide funds themselves (they don’t do that). And while I have long had issue with the price of WMM films and acquisitions, because schools like pov u are essentially priced out of owning or even exhibiting many of their films, their work not only ensures that women’s films get made but that those films are permanently archived.

intersectional support. Much of the minimal budget for Watermelon Woman came through Women Make Movies, a feminist media group that helps ensure the production, promotion, distribution, etc. of female directors and films by and for women. As the fiscal sponsor, WMM helped Dunye secure funding she would not otherwise have been able to receive though they did not provide funds themselves (they don’t do that). And while I have long had issue with the price of WMM films and acquisitions, because schools like pov u are essentially priced out of owning or even exhibiting many of their films, their work not only ensures that women’s films get made but that those films are permanently archived.

First Run Features was also instrumental in the distribution of Watermelon Woman. FRF is one of the largest distributers of independent and documentary films in the U.S. and they have considerable holdings of queer and international films as well as films by people of color. They are also the distributers of a collection of Dunye’s early work which predates Watermelon Woman and includes: Greetings from Africa, The Potluck and the Passion, An Untitled Portrait, Vanilla Sex, She Don’t Fade, and Janine. Taken together, these shorts represent some of the key issues in lesbian experience from a black lesbian vantage point including: sexuality, family, interracial dating, and the potluck.

Dunye’s collection of early works was also debuted on the West Coast at the Queer Women of Color Film Festival which presents and promotes the work of women of colors from all racial backgrounds to an audience of white and women of color, the gay community, and its allies. Dunye also spoke at the event, further expanding the reach of her unique cinematic form, her stories of a black lesbian experience, and inspire a new generation of women of color filmmakers.

color, the gay community, and its allies. Dunye also spoke at the event, further expanding the reach of her unique cinematic form, her stories of a black lesbian experience, and inspire a new generation of women of color filmmakers.

Despite her modesty about it, Dunye has always been a director who understands the necessity of history and the blending of historiographic and cinematic form. Not only did Watermelon Woman and several of her shorts combine these, but her next major film project Stranger Inside did as well.

Stranger Inside moved out of archival examination and into oral history. Dunye and her partners worked with inmates to collect stories about their experiences that were most important to them. As Dunye began to develop the script for her sophmore effort, she also asked inmates to workshop the characters and scenes with her in order to make them as authentic a reflection of prison life as she could.  Rather than turning the experience into spectacle, Dunye wanted to give voice to the inmate experience and to respect the voices she found within the prison walls.

Rather than turning the experience into spectacle, Dunye wanted to give voice to the inmate experience and to respect the voices she found within the prison walls.

Stranger Inside follows the tragic decision of a teenage inmate searching for her mother. Treasure Lee is a young inmate with only a few months left on her sentence. She and another friend have been sent to jail for gang activity, both of them having experienced the cycle of racism-poverty-and incarceration that is all too predicatable in N. America’s forgotten neighborhoods. Unlike her friend, who uses these last few months to start an education and develop a plan for her life away from the gangs, Treasure commits a capital offense in order to stay in prison and join the mother she barely remembers. The film has a tragic twist to it that I will not reveal but one that left my students stunned and silent as the film came to a close in our joint showing with a sociology of race course.

When the film was first introduced to me by both Netflix and a graduate student, both called it a “queer film.” I would argue that most of the characters are not queer and it is unclear if Treasure is either or if she just getting her needs met on the inside. Either way, the film once again expands discussion of sexuality through the lens of prison hierarchies and lifers as well of shifting the meaning of a “woman’s prison” or “lesbians in prison” film.

This film also branches out from the black-white binary of Dunye’s earlier work by including Asian and Latina characters. I have some concerns about how the Asian woman comes across in this film as well as how the femme does, but the complexity of the script and the direction are such that I continue to mull these concerns over rather than landing on a single reading. That perhaps is the best sign of Dunye’s craft, that it makes you think and sticks with you in ways that keeps changing.

(I would argue that her religious symbolism is far less complex or thought provoking however.)

Dunye herself is quick to remind others that she is not alone in the struggle to represent positive black lesbian  experiences in film. She pointed to Whoopi Goldberg’s role in Boys on the Side and Latifah’s role in Set It Off as two groundbreaking mainstream examples that inspire her. These films are important because one was made for a mainstream independent film audience and the other was made for mainstream black audiences both of whom might not crossover to watching films about black lesbians. The inclusion of black lesbian characters in these films then expands the knowledge of its audience and exposes them to identities that are normally hidden to them. This is what Dunye is trying to accomplish with her own work.

experiences in film. She pointed to Whoopi Goldberg’s role in Boys on the Side and Latifah’s role in Set It Off as two groundbreaking mainstream examples that inspire her. These films are important because one was made for a mainstream independent film audience and the other was made for mainstream black audiences both of whom might not crossover to watching films about black lesbians. The inclusion of black lesbian characters in these films then expands the knowledge of its audience and exposes them to identities that are normally hidden to them. This is what Dunye is trying to accomplish with her own work.

She also places her work within the context of other black lesbian filmmakers such as: Jocelyn Taylor (who plays Cheryl’s bestfriend in Watermelon Woman), Leah Gilliam, Dawn Suggs, Shari Frilot, Michelle Parkerson, and Yvonne Welbon . She credits all of these women as a co-creative circle that critiques, curates, and lends love and support to one another’s projects. Yvonne Welbon’s work inspired me to write these film posts in the first place and I will be doing a post on all of these women as lesser known black women directors as part of this series.

. She credits all of these women as a co-creative circle that critiques, curates, and lends love and support to one another’s projects. Yvonne Welbon’s work inspired me to write these film posts in the first place and I will be doing a post on all of these women as lesser known black women directors as part of this series.

And echoing a running, and yet unintentional thread, in the Black Herstory Posts, Dunye is a college professor. She currently teaches at Temple where I have no doubt a whole new group of intersectionally oriented cinematic historiographers are being born every day.

——

images:

- watermelon woman DVD cover

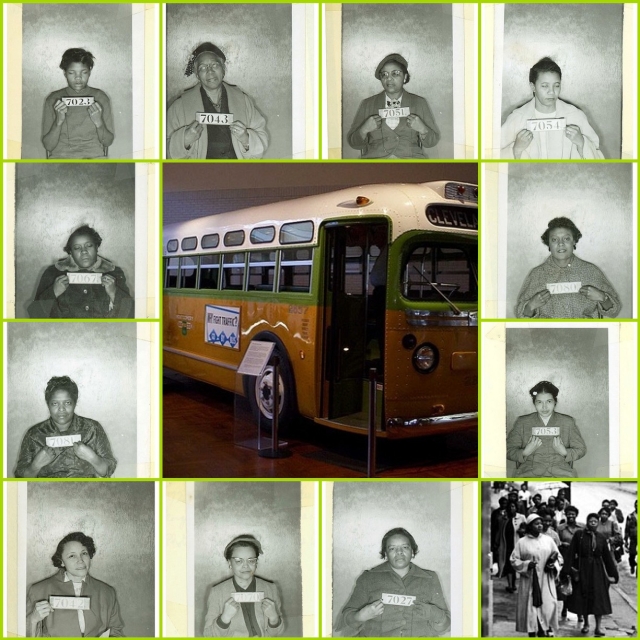

- lesbian history archive image

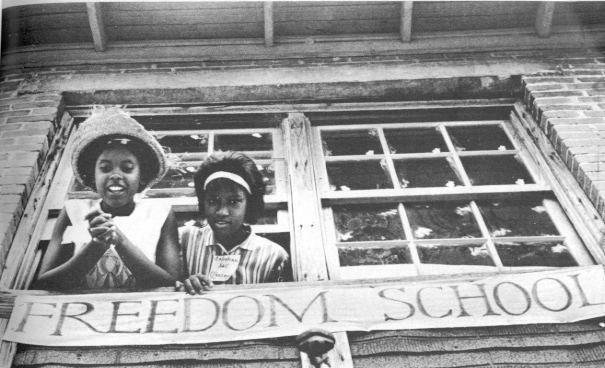

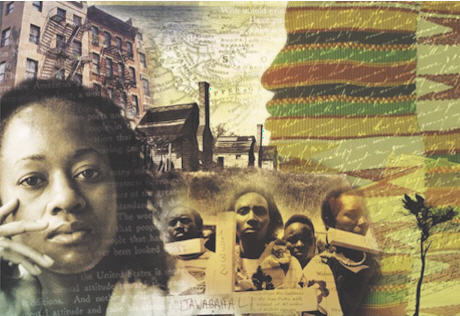

- black gay and lesbian archive project brochure cover

- Dunye and her ex-girlfriend

- stranger inside DVD cover

- Latifah movie still from Set it Off

- Whoopi, Barrymoore, and Parker movie still Boys on the Side

- Leah Gilliam in Saphire and the Slave Girl